Injection Blow Molding (IBM) is one of the cleanest, most precise ways to produce small-to-medium plastic containers, especially when neck accuracy, clarity, and repeatability matter.

But getting predictable performance from an IBM line comes down to one thing: understanding the machine’s components and how each one influences preform quality, blow behavior, and final part performance.

Most online explanations conflate IBM with extrusion blow molding or omit the machine's anatomy entirely.

That’s a problem, because IBM lives or dies by the condition and alignment of a few critical parts: the injection unit, core rods, neck rings, rotary table, blow molds, and the systems that control temperature, pressure, cooling, and air delivery.

This guide fixes that.

You’ll get a complete, engineer-level breakdown of every major component in an injection blow molding machine, how the 3-station process actually works, where tolerance is won or lost, what wear looks like in the field, and how to select a machine that fits your resin, volume, and container geometry.

If you want accurate, practical information about IBM machine parts, this is the guide you’ve been looking for.

Key Takeaways

IBM is a 3-station process, injection, blow, and cooling, and part quality depends heavily on core rod temperature, alignment, and melt preparation.

The most critical machine parts are the injection unit, core rods, neck rings, preform mold, rotary table, and blow mold. Wear on any of these shows up immediately as ovality, thread defects, haze, or wall-thickness variation.

IBM and extrusion blow molding utilize completely different hardware and materials; IBM is chosen for precision necks and clarity, rather than large hollow parts.

HDPE, PP, PETG, and select PC grades run in IBM. Standard PET requires Injection Stretch Blow Molding (ISBM), not IBM.

Melt stability inside the injection unit controls preform consistency — MD Plastics’ screws, valves, and melt-monitoring tools help processors improve clarity, wall uniformity, and shot repeatability.

Injection Blow Molding in One Look

Injection blow molding runs in a continuous three-station loop. Each station shapes part of the bottle’s final geometry, and each relies on precise temperature and timing to avoid defects.

Station 1: Injection: Forming the Preform on the Core Rod

At the first station, molten polymer is injected into a preform mold directly around a chilled core rod. The core rod defines the internal diameter, while the neck ring forms the threads and sealing surface.

A good preform at this step determines how evenly the material will stretch during blowing.

Indexing Transfer: Rotary Table Movement

Once the preform is set, the rotary turret indexes the entire core-rod/preform assembly to the next station.

Here, alignment and surface temperature are critical; a core rod with incorrect temperature causes uneven blowing, wall-thickness variation, haze, or ovality — not stretch-direction variation.

Station 2: Blow Molding: Expanding to Final Shape

The blow mold closes around the preform, and compressed air enters through the core rod.

The hot preform expands uniformly against the mold walls (no axial stretch as seen in ISBM), forming the bottle or container geometry with controlled wall distribution and clarity.

Station 3: Cooling & Ejection: Locking in Final Dimensions

With the part fully expanded, the system manages cooling through the blow mold and the core rod. Proper cooling prevents ovality, sink, and finish distortion.

Once stable, the mold opens, and automation removes the part before the core rod returns to the injection station.

IBM’s three-station method produces high-precision neck finishes, excellent clarity, and highly uniform wall thickness, making it the preferred choice for pharmaceutical, cosmetic, and small food-grade containers.

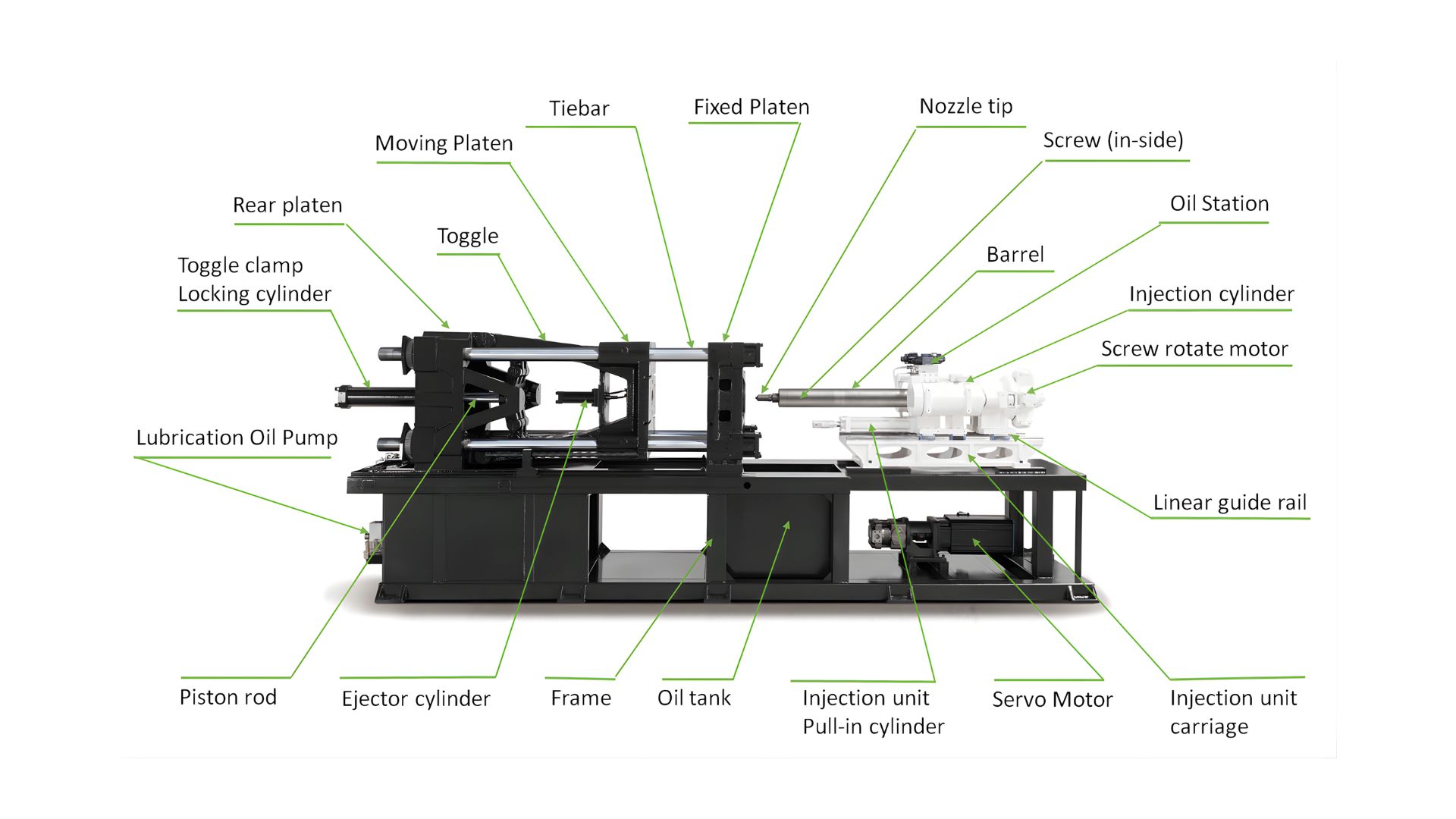

The Anatomy of an Injection Blow Molding Machine

Injection Blow Molding (IBM) is unforgiving. The melt must be prepared perfectly, the preform must be dimensionally correct before transfer, and every station must stay synchronized.

To understand why IBM produces unmatched neck finishes and clarity, you need to understand what each component actually governs inside the cycle.

Below is a functional breakdown of every major IBM machine component, including the engineering dependencies, failure symptoms, and what tolerances matter most.

1. Injection Unit (Where Melt Quality Begins)

The injection unit determines everything about preform consistency. Poor melt prep cannot be corrected downstream.

Core elements:

Barrel: Sets thermal profile that defines melt viscosity.

Screw: Melts, mixes, and meters shot volume. Geometry affects residence time, shear profile, and material clarity.

Non-Return Valve (NRV): Shot integrity; leakage causes preform short shots.

Nozzle: Provides clean melt transfer and thermal stability at the gate.

What it controls:

Melt temperature uniformity

Preform fill balance

Clarity (shear + thermal history)

Neck-finish dimensional consistency

Thread-forming definition at the preform gate

Failure symptoms:

Stringing or splay

Preform short shots

Inconsistent wall thickness

Haze caused by thermal fluctuations

Weight variability

2. Core Rod Assembly (The Most Critical Part in IBM)

The core rod sets the internal shape, supports the preform during transfer, and delivers blowing air.

It is also the single component that touches the part in every station.

Functions:

Defines the inside diameter and stretch ratio

Maintains preform geometry during indexing

Contains cooling channels that freeze the wall structure and clarity

Provides the air pathway for blowing

Why it matters:

Any deviation in surface finish, straightness, or temperature uniformity instantly appears in the bottle as ovality, haze, or inconsistent wall distribution.

Wear symptoms:

Wall thickness shift (one side heavier)

Cloudiness near the base

Sink around the neck-support ring

Sticking during transfer

High-end IBM lines treat the core rod as a precision tool, not a consumable.

3. Neck-Ring / Finish Tooling (Where Sealing Performance Is Made or Lost)

The neck finish, threads, sealing surface, and tamper band are the most controlled features on a bottle. IBM excels here because the neck ring forms the finish before blowing.

Functions:

Shapes threads to cap/closure specs

Holds the preform securely during transfer

Maintains concentricity relative to the core rod

Failure symptoms:

Flash at the neck

Misaligned threads

Poor cap fit/leak failures

“High neck” or “short neck” dimensional drift

A worn neck ring is one of the most common causes of packaging line rejection.

4. Preform Mold (Defines How Well the Bottle Will Blow)

Unlike extrusion blow, IBM begins by forming a precision preform.

Functions:

Controls the preform wall profile → directly determines final bottle wall thickness

Steel grade affects cooling speed and mold life

Venting prevents gas traps and incomplete fill

Cooling circuits stabilize the preform so it survives the transfer

Failure symptoms:

Preform warpage → bottle distortion

Short shots

Poor clarity from hot spots

Thread distortion can stem from neck-ring misalignment, uneven cooling, thermal imbalance, or injection pressure spikes.

IBM’s tight downstream control depends on a stable, dimensionally correct preform.

5. Rotary Indexing Table / Turret (The Synchronization Backbone)

This mechanism rotates the core rod assemblies between Injection → Blow → Ejection.

Engineering requirements:

High positional accuracy

Repeatable indexing timing

Tight thermal control around the core-rod mounts

Smooth acceleration to avoid deflection of hot preforms

Failure symptoms:

Misaligned blow mold closure

Seam shift on finished bottles

Stretched or deformed preforms during transfer

A sloppy indexing system ruins process repeatability.

6. Blow Mold (Final Part Geometry + Cooling Authority)

The blow mold is where clarity, contour accuracy, and surface finish are set.

Functions:

Governs wall distribution during expansion

Pulls heat out fast → determines cycle rate

Defines surface texture, ribs, and logos

Controls base formation and push-up stability

Failure symptoms:

Oval bottles (uneven cooling)

Stiff base / soft base variation

Surface haze

Parting-line mismatch

With IBM, the blow mold is less about forming and more about managing heat extraction.

7. Blow Air System / Blow Pin Pathway (Stretch + Expansion Behavior)

Blow air enters through the core rod, making the pathway design critical.

Controls:

Stretch behavior of the hot preform

Final wall thickness distribution

Crystal clarity (air timing + pressure curves)

Base formation

Failure symptoms:

Uneven expansion

Weak shoulders

Cloudy panels

Air entrapment marks

The airflow profile is as important as the mold temperature.

8. Clamping System (Dual-Function: Injection & Blow)

IBM uses two distinct clamps:

Injection Clamp

Holds the preform mold closed during filling

Must handle injection pressures without deflection

Blow Clamp

Holds the blow mold closed during high-pressure expansion

Alignment affects seam visibility and ovality

Failure symptoms:

Flash on neck or body

Parting-line mismatch

Seam thickening

9. Cooling System (The Cycle-Time Limiter)

Cooling is more complex than in injection molding because:

Preform cools on a metal core rod

The bottle cools inside the blow mold

Heat extraction must be consistent across three stations

Turret cooling is also critical to ensure consistent core-rod temperatures across stations.

Cooling paths include:

Core rod cooling

Neck ring cooling

Blow mold cooling

Injection mold cooling

Failure symptoms:

Ovality

Inconsistent transparency

Cycle-time drift

Blow mold sticking

10. Hydraulic / Pneumatic Systems (Motion Accuracy = Part Accuracy)

These systems' power:

Mold open/close

Turret rotation

Core rod movement

Neck ring slides

Ejectors

Take-out

Failure symptoms:

Slow cycle

Index lag

Incomplete clamp

Flash or deformation

Random downtime

Pneumatic stability especially affects blow timing and bottle clarity.

11. Control System (PLC / HMI: Where Repeatability Lives)

A modern IBM PLC governs:

Barrel temperature zones

Injection pressures & speeds

Transfer timing

Blow pressure profile

Mold cooling sequencing

Alarms and diagnostics

A weak control system equals:

Weight drift

Inconsistent neck dimensions

Unpredictable startup/shutdown behavior

Process repeatability = machine control discipline.

12. Take-Out / Automation (Where Damage Often Happens)

A good IBM take-out system removes hot bottles without distortion.

Functions:

Eliminates operator variability

Ensures uniform cooling after release

Supports high cavitation without part damage

Failure symptoms:

Oval finish

Scuff marks

Soft-base deformation

Random reject spikes

With the core IBM components identified, it helps to contrast them with extrusion blow systems. Many processors use the terms interchangeably, but the equipment, tooling, and part capabilities are fundamentally different.

Injection Blow vs Extrusion Blow Molding

Injection blow molding (IBM) and extrusion blow molding (EBM) both create hollow plastic parts, but the machine architecture, tooling, material behavior, and achievable tolerances are fundamentally different.

This comparison breaks down the differences in a way that engineers can evaluate at a glance.

Preform vs Parison Formation

IBM:

A fully formed preform is injection molded around a precision core rod.

The neck finish is created in the injection station and remains dimensionally fixed.

Melt quality and shot consistency directly affect clarity and wall uniformity.

EBM:

A molten parison is extruded vertically from a die head.

Wall thickness depends on die gap control, melt strength, and parison programming.

Neck geometry is formed during pinch-off, not injection—lower accuracy.

Key Difference: IBM uses a solid, molded preform; EBM uses a molten, hanging parison.

Core Rod vs Die-Head Extruder

IBM:

Core rods set internal diameter, stretch behavior, and final bottle symmetry.

Cooling channels inside the rod stabilize neck and shoulder formation.

Coordinated timing between stations maintains dimensional repeatability.

EBM:

The die head creates the parison and may incorporate parison programming for thickness control.

No core rod, shape forms entirely by inflation and mold geometry.

Highly dependent on melt strength and extrusion stability.

Key Difference: IBM’s core rod creates consistency; EBM relies on melt strength and timing.

Tooling: Injection + Blow Molds vs Single Blow Mold

IBM:

Requires two tool sets:

Injection preform mold

Blow mold (final shape)

Higher tooling precision allows better cosmetic detail and dimensional accuracy.

EBM:

Uses a single blow mold with a pinch-off region.

Tooling is simpler, but less detailed flash removal is usually required.

Key Difference: IBM tooling is more complex but delivers substantially better finish quality.

Material Compatibility

IBM:

Best with materials requiring high clarity and precision:

PP

PETG

PC

HDPE (for some applications)

EBM:

Best with resins with high melt strength:

HDPE (dominant)

PP

PVC

Multilayer barrier structures (EVOH)

Key Difference: IBM = clarity + precision; EBM = strength + wall distribution.

Neck Finish Accuracy & Part Quality

IBM:

Neck threads and sealing surfaces formed during injection—high accuracy.

Excellent dimensional repeatability.

Ideal for products requiring leak-proof or torque-controlled closures.

EBM:

Finish formed during mold pinch-off—lower accuracy.

Slight ovality or flash can occur depending on the mold condition.

Key Difference: IBM dominates where closure performance matters (pharma, personal care).

Typical Applications

IBM:

Small to medium bottles

Pharmaceutical & nutraceutical containers

Eye-dropper and spray bottles

Personal care packaging

High-clarity cosmetic containers

EBM:

Large bottles (detergent, milk, oils)

Automotive ducts

Jerry cans

Industrial drums

Larger hollow goods

Energy Use, Tooling Cost & Production Efficiency

IBM:

Higher tooling cost due to dual mold sets and precision cores.

Lower material waste (no flash).

Superior repeatability → lower reject rates.

EBM:

Lower tooling cost.

Higher scrap due to flash and trimming.

More forgiving of large part sizes.

At-a-Glance Comparison Table

Feature / Requirement | Injection Blow Molding (IBM) | Extrusion Blow Molding (EBM) |

|---|---|---|

Formation | Injection-molded preform on core rod | Extruded parison from die head |

Neck Finish | Molded in injection—highest accuracy | Pinch-off formed—moderate accuracy |

Core Element | Core rod controls ID, stretch, and cooling | No core rod; relies on parison control |

Tooling | Injection + blow mold (dual) | Single blow mold (+ trim) |

Wall Uniformity | Very consistent (preform-based) | Variable (depends on parison programming) |

Clarity / Cosmetics | High (PETG/PP/PC) | Moderate |

Materials | PP, PETG, PC, clarified HDPE (select grades) | HDPE, PP, PVC, multilayer EVOH |

Part Size | Small–medium | Small–very large |

Scrap | Low (no flash) | Higher (flash/trim) |

Tooling Cost | Higher (precision cores) | Lower |

Use IBM when neck accuracy, clarity, and repeatability are non-negotiable (pharma, personal care). Use EBM for larger volumes/sizes and when wall programming and cost take priority (detergent, jerry cans).

With the differences between IBM and EBM clear, the next question is one engineers ask early in any project: Which materials actually run well in blow-based processes and why?

That’s where resin behavior, melt strength, and clarity requirements start to narrow the options.

Let’s break down the blow-extrusion materials that consistently deliver reliable processing and part performance.

Blow Extrusion Materials: What Runs Well and Why

Blow molding, whether extrusion blow or injection blow, depends heavily on melt strength, viscosity behavior, and cooling response. Not every resin can form a stable parison or withstand stretch without thinning unevenly.

Below is a concise, engineer-level breakdown of the resins that consistently perform well in blow-based processes and the reasons why.

1. HDPE (High-Density Polyethylene)

Why it runs well:

Naturally high melt strength → holds shape during parison formation

Excellent ESCR (environmental stress crack resistance)

Predictable cooling and shrinkage behavior

Used for: Detergent bottles, milk jugs, automotive ducts, and industrial containers.

EBM vs IBM:

EBM: Extrusion blow molding (EBM). HDPE is the workhorse resin for EBM due to its stability during free-hanging parison formation.

IBM: Limited, HDPE can run in IBM, but clarity is poor, and wall control is less precise.

2. PP (Polypropylene)

Why it runs well:

High stiffness and heat resistance

Good hinge strength

Lower density = lightweight parts

Used for: Thin-walled packaging, clarified personal-care bottles, and technical parts requiring rigidity.

EBM vs IBM:

EBM: Works well but requires more parison control due to lower melt strength than HDPE.

IBM: Runs well for small bottles with precise neck finishes and better clarity than HDPE.

3. PETG (Glycol-Modified PET)

Why it runs well:

Excellent clarity

Good impact resistance

Low haze and high gloss

Used for: Cosmetic packaging, medical tubes/containers, and premium small bottles.

EBM vs IBM:

IBM: Preferred, PETG provides high clarity without stretch-blow equipment.

EBM: Less common due to lower melt strength.

4. PVC (Polyvinyl Chloride)

Why it runs well:

Good strength and clarity

High melt elasticity in many grades

Stable wall distribution during inflation

Used for: Specialty bottles, chemical containers, and technical parts.

EBM vs IBM:

EBM: Common for technical-grade containers.

IBM: Possible but less common due to heat sensitivity during preform molding.

5. PC (Polycarbonate)

Why it runs well:

Extremely high impact strength

Good clarity

Dimensional stability after blowing

Used for: Medical containers, technical housings, safety-related components.

EBM vs IBM:

IBM: Preferred, PC benefits from preform-based precision and better thermal control.

EBM: Possible but requires very tight temperature management.

6. Multilayer / Barrier Resins (EVOH, Tie-Layers)

Why they run well:

Provide gas barrier performance for food, fuel, and chemical packaging

Enable long shelf life and odor control

Used for: Fuel tanks, food-grade bottles, specialty pharma packaging.

EBM vs IBM:

EBM: Dominant, multilayer structures are typically co-extruded during parison formation.

IBM: Rare, IBM isn’t typically used for barrier multilayer structures due to tooling and preform complexity.

Where Each Resin Fits: IBM vs EBM

Resin | Best for EBM | Best for IBM | Why |

|---|---|---|---|

HDPE | ✔✔✔ | ✔ (limited) | High melt strength ideal for parisons |

PP | ✔✔ | ✔✔ | Good stiffness; workable in both |

PETG | ✔ (limited) | ✔✔✔ | High clarity, great for preform-based forming |

PVC | ✔✔ | ✔ | Heat-sensitive but blow-friendly |

PC | ✔ (technical only) | ✔✔✔ | Demands tight thermal control |

EVOH ML | ✔✔✔ | ✖ | Co-extrusion is favored for multilayer barriers |

Choosing the right resin matters as much as choosing the right machine—material behavior defines parison stability, stretch response, wall uniformity, and clarity long before the mold ever closes.

Note: Injection stretch blow molding (ISBM) is a separate process used for PET bottles and should not be confused with IBM.

Tolerances, Finish & Typical Applications for Injection Blow Molding

Injection blow molding exists for one primary reason: precision. When small and medium-sized containers need accurate neck finishes, repeatable wall thickness, and near-injection-molding-level clarity, IBM consistently outperforms other blow molding methods.

Why IBM Excels at Tight Tolerances

Unlike extrusion blow molding, IBM begins with a fully injection-molded preform created on a core rod with controlled dimensions, cooling, and material distribution. This gives IBM several built-in accuracy advantages:

Neck finish is molded, not formed, so threads, sealing surfaces, and shoulder geometry stay within tight tolerances.

Wall thickness starts uniformly due to the preform’s injection-defined geometry.

Minimal flash and parting-line defects, because there’s no parison pinch-off step.

Core rod stability ensures the preform stays centered during blowing, reducing ovality.

The result: dimensional repeatability that’s significantly better than extrusion blow.

Superior Cosmetic and Optical Finish

IBM parts typically achieve higher clarity and gloss because:

The injection-molded preform has a smooth, fully packed surface.

Stretch during blowing is controlled by the core rod’s thermal profile.

No parison sag or deformation can introduce haze.

For PETG, PP, PC, and certain clarified resins, IBM consistently produces clearer, more uniform containers than EBM.

Where IBM Is the Best-Fit Process

IBM shines in markets where precision + aesthetics + functional sealing matter:

Pharmaceutical & Healthcare

Dropper bottles

Nasal spray vials

Diagnostic sample containers

Sterile packaging

Tight neck tolerances ensure secure closures, dosage accuracy, and regulatory compliance.

Personal Care & Cosmetics

Travel-size bottles

Lotion containers

High-clarity PETG bottles

These products rely heavily on surface quality and consistent wall thickness.

Food & Beverage

Flavoring bottles

Concentrates

Single-serve items

IBM delivers consistent neck threads to guarantee leak-free sealing.

Technical / Specialty Packaging

Laboratory containers

Chemical dispensing bottles

High-precision dosing bottles

Uniform walls support predictable drop strength and performance.

Why Cap & Closure Compatibility Is a Major IBM Advantage

Closures are often the most unforgiving part of a package. A slight issue with the finish can cause:

Leaks

Over-torquing

Cross-threading

Poor tamper-evidence performance

IBM’s ability to mold the finish directly from the injection cavity ensures:

Accurate thread pitch

Consistent sealing of land

Stable neck ID/OD

Minimal ovality

This is a major reason IBM dominates pharmaceutical and cosmetic packaging.

IBM is chosen not because it’s the cheapest or fastest method, but because it delivers the precision, clarity, and dimensional stability required for small–medium bottles with strict functional and cosmetic requirements.

Common Wear Parts & Failure Symptoms

Your Maintenance Cheat Sheet!

Even the best injection blow molding machines drift out of spec over time, not because of bad operation, but because the parts that define accuracy slowly wear.

This section gives you a fast, engineering-first diagnostic map: what wears, why it wears, the defects it causes, and what to check during maintenance.

1. Core Rod Wear (Highest-Impact Wear Component)

The core rod determines preform wall uniformity, clarity, and final bottle geometry. As the rod wears, even slightly, the effects show up immediately in part quality.

Wear Causes

Repeated thermal cycling

Micro-abrasion from resin (especially glass-filled)

Poor cooling-water quality is causing internal scaling

Contact wear at transition points

Failure Symptoms

Wall thickness is drifting toward one side

Loss of clarity or internal flow marks

Ovality after blowing

Stretch behavior inconsistency

What to Inspect

Rod diameter at multiple points

Surface polish (Ra) stability

Cooling-channel flow rate

Alignment with the neck ring and blow mold

Maintenance Interval: Inspect every 1–3 months, depending on resin and volume.

2. Neck-Ring / Finish Tooling Wear

The neck ring forms the finish, which is the most functionally critical feature of IBM packaging. Small wear = big problems.

Wear Causes

Mechanical impact during opening/closing

Overheating

Resin leakage at the finish area

Repeated contact with the core rod

Failure Symptoms

Thread flash

Cross-threading or mis-threading

Dimensional drift → leaking closures

Finish ovality

What to Inspect

Thread profile

Sealing-land flatness

Parting-line condition

Fit against cothe re rod

Maintenance Interval: Inspect every 2–6 weeks on high-volume pharmaceutical/consumer lines.

3. Blow Mold Wear or Cooling Channel Blockage

Blow molds rarely fail structurally, but cooling deterioration causes more defects than tooling wear itself.

Wear/Blockage Causes

Mineral scale in cooling lines

Corrosion (especially in hard water environments)

Impact wear at parting-line surfaces

Cavitation erosion from aggressive cooling

Failure Symptoms

Ovality

Inconsistent wall distribution

Random clarity streaks from uneven cooling

Slow cycle time from poor heat extraction

What to Inspect

Cooling-channel flow and temperature differential

Parting-line wear

Mold-base flatness

Localized hotspots using IR measurement

Maintenance Interval: Descale quarterly; inspect mold surfaces every 4–8 weeks.

4. Injection Nozzle or Non-Return Valve (NRV) Wear

The injection side defines the preform quality, which defines everything that happens downstream. A worn nozzle or NRV disrupts melt delivery long before other defects appear.

Wear Causes

Abrasive resin grades (GF, mineral-filled)

High backpressure settings

Excessive decompression

Poor melt filtration upstream

Failure Symptoms

Short shots

Stringing/drooling at injection

Inconsistent shot size

Color streaking from poor mixing

What to Inspect

Valve sealing land

Nozzle tip surface condition

Valve spring response (for check valves)

Melt pressure stability

Maintenance Interval: Inspect every 1–2 months; replace valves annually on high-volume lines.

5. Hydraulic & Pneumatic System Drift

IBM relies heavily on controlled motion between stations. Hydraulic or pneumatic issues show up as timing and symmetry defects, not just speed issues.

Wear Causes

Seal failure

Pressure regulator drift

Valve is sticking from contamination

Air/oil temperature instability

Failure Symptoms

Slow or uneven indexing

Incomplete mold closure → seam marks or flash

Blow-pin timing issues

Variability in cycle time

What to Inspect

Cylinder seal condition

Pressure/flow stability

Valve response time

Air quality (dry, filtered)

Maintenance Interval: Weekly pressure checks; full system inspection quarterly.

These wear patterns are predictable, and once you know what each component controls, IBM troubleshooting becomes faster, cleaner, and far more repeatable.

Selecting an Injection Blow Molding Machine

Most IBM machines look similar from the outside: three stations, a turret, a clamp. But the performance spread between models is huge, and it comes down to a handful of specs that directly affect bottle geometry, clarity, and output rate.

Here’s how experienced processors evaluate a machine not by brochure numbers, but by what shapes day-to-day production.

Start With the Mold, Not the Machine

Every IBM decision begins with the part:

Bottle size

Neck finish

Wall-thickness target

Clarity expectations

Annual volume

Once that’s fixed, the machine specs fall into place.

Clamp Capacity: Can It Hold the Mold Itself?

IBM needs two independent clamps.

Processors usually size them based on:

Injection clamp → must resist cavity fill pressure (preforms with thick bases need more).

Blow clamp → must hold long enough for the preform to stretch and settle without tempting flash.

Most plants oversize tonnage “for safety” and end up with slower cycles. The goal isn’t brute force; it’s repeatable closure.

Shot Capacity: The Actual Constraint Nobody Talks About

The bottle’s entire mass is created in the preform stage. IBM requires extremely tight shot-size repeatability because even small weight variations create downstream blowing inconsistencies.

If shot size is mismatched:

Too small → short shots, base collapse, or poor material distribution

Too large → overheated melt, excessive residence time, and haze

This is usually the first bottleneck when companies want to increase cavitation.

Core-Rod Count: Throughput Lives or Dies Here

Core rods determine:

How many bottles exist per cycle

How stable the neck geometry is

Whether cooling stays uniform from rod to rod

When one rod runs hotter than the others, ovality shows up.

This is why processors value machines with balanced internal cooling more than machines with flashy screens.

Indexing System: The Real Cycle-Time Governor

The turret isn’t just a rotating plate.

Indexing needs to:

Move fast

Land precisely

Avoid micro-vibrations that print seam marks into the bottle

Older hydraulics drift with heat.

Modern servo kinematics maintain position even as cycle time ramps up.

Cooling Capacity: The Quiet Variable That Fixes or Ruins Tolerances

IBM bottles are small, but tolerances are not.

When the cooling capacity doesn’t match the mold layout:

Neck finishes ovalize

Sidewalls haze

Preforms crystallize unevenly

Processors often upgrade chillers before they upgrade machines for this reason.

Cavitation Strategy: Not “More Cavities = Better.”

More cavities raise output, but also:

Increase clamp load

Reduce thermal spacing

Tighten mold-flow balance

Demand stricter core-rod uniformity

For personal-care or pharma bottles, plants often choose fewer cavities with tighter control over “maximum cavitation.”

Controls & Automation: Where Repeatability Is Won

On IBM machines, control systems matter more than raw tonnage:

Temperature stability

Preform injection profile

Blow timing

Turret dwell times

Cooling sequencing

The difference between an average machine and an excellent one is usually in the screens, not the steel.

Automation (take-out, leak test, trimming, vision) keeps operators from deforming warm bottles, especially thin-walled ones.

Short Selection Logic

If your part is cosmetic or requires tight neck fits → prioritize core-rod cooling and high-resolution controls.

If your part is larger → prioritize shot size and blow-clamp rigidity.

If your part is high volume → prioritize cavitation + indexing speed.

If your material is clarity-sensitive (PP, PETG) → prioritize melt prep + precise injection control.

Most IBM decisions start with tooling and machine hardware, but the melt entering the preform mold determines clarity, thickness stability, and whether every cavity behaves the same.

This is where MD Plastics strengthens the injection side of IBM systems

How MD Plastics Strengthens Melt Preparation for Injection Blow Molding

Injection blow molding succeeds or fails at Station 1 the moment the preform is injected onto the core rod. If the melt isn’t stable, uniform, and delivered with repeatable pressure, every downstream step (stretching, blowing, cooling) has to compensate for it.

That’s where MD Plastics’ engineering focus becomes directly relevant to IBM processors.

1. Why the Injection Unit Dictates Preform Quality

IBM relies on the preform to establish:

Wall-thickness balance

Clarity and gloss

Stretch behavior during blowing

Neck-finish precision

The final bottle’s dimensional stability

If the melt entering the preform mold fluctuates in temperature, viscosity, or homogeneity, those defects show up as haze, weak shoulders, uneven stretch ratios, or thread inconsistencies.

IBM is more sensitive to melt prep than EBM, because the preform is the bottle.

2. MD Plastics Components That Improve Melt Conditioning in IBM

MD Plastics focuses on the parts of the injection unit that directly affect how a preform fills and freezes:

Custom-engineered screws

Designed for uniform shear and controlled melt development, critical for clarity-sensitive materials like PP, PETG, and PC.

Precision barrels

Improve thermal stability, reducing melt temperature wave patterns that distort the preform geometry.

MDP™ Non-Return Valves (NRVs)

Deliver consistent shot volume and eliminate backflow key for multi-cavity IBM tools, where every core rod demands the same dose.

High-performance nozzle tips

Maintain melt integrity at the entry of the preform mold, preventing stringing, cold slugs, or premature gate freeze.

These upgrades address exactly the variables that compromise IBM bottle performance.

3. How Melt Stability Translates Into Better Blow Results

Stable melt preparation leads to measurable improvements across Stations 2 and 3:

Balanced preform → balanced stretch → balanced bottle

Uniform melt → higher clarity, fewer flow lines

Consistent injection pressure → predictable expansion inside the blow mold

Reduced thermal spikes → fewer weak shoulders and thin wall sections

In IBM, every bottle “inherits” the melt quality that entered the preform mold. Fix that, and downstream variation drops immediately.

4. Real-Time Melt Monitoring: Detect Problems Before the Bottle Shows Them

MD Plastics’ monitoring tools, Melt-Profiler™, Melt-IQ®, and Temp-Sense™, give IBM processors data that normally stays hidden inside the barrel:

True melt temperature, not barrel heater readings

Melt pressure behavior during plasticizing and injection

Viscosity signatures that reveal resin variation or moisture issues

Early indicators of screw, NRV, or barrel wear

This allows plants to correct melt instability before it turns into core-rod imbalance, haze, or oval bottles at the takeout station.

5. Retrofit Upgrades for Existing IBM Machines

Most IBM machines run for decades. Many of them can be significantly improved by modernizing only the injection side:

Upgraded plasticating assemblies

New NRVs and injection tips

Enhanced melt monitoring

Replaced or reconditioned barrels

Improved melt-density control

The result is a machine that produces cleaner preforms, clearer bottles, steadier neck finishes, and fewer unplanned stoppages, without replacing the entire system.

See what your preform melt is really doing.

MD Plastics takes a scientific, hands-on approach: we study your machine, tooling, and melt path to discover, develop, and engineer solutions that remove upstream variability.

For IBM processors, that means stabilizing the injection unit so preforms fill cleanly and repeatably, before the core rod ever indexes.

If clarity, wall uniformity, or shot repeatability are limiting your IBM line, ask for an analytical melt review. We’ll evaluate your process and engineer the best-fit, durable solution, not just a part.

Conclusion

Injection blow molding succeeds or struggles based on three fundamentals: how the machine is built, how the melt is prepared before injection, and how well the tooling manages heat and alignment across all stations.

When those elements work together, IBM delivers unmatched neck-finish precision, excellent clarity, and repeatable wall-thickness control, making it the preferred choice for pharmaceutical, personal-care, and premium packaging.

If your process is hitting limits in clarity, consistency, or cycle efficiency, the most effective place to start is the injection unit. That’s where melt quality is set and where MD Plastics provides engineering support, upgraded components, and real-time melt-monitoring tools to stabilize performance before the blow station ever closes.

Want proof in production?

Watch our short video on increasing profits with better melt control.

See how real melt data and engineered plasticating components improve clarity, neck-finish accuracy, and shot consistency on IBM lines.

FAQs

1. What are the main parts of an injection blow molding machine?

An IBM system uses three coordinated stations—injection, blow, and cooling—supported by key components such as the injection unit, core rods, neck rings, injection and blow molds, rotary indexing table, cooling circuits, and control systems.

2. Which materials run best in blow extrusion and injection blow molding?

HDPE, PP, PETG, PVC, and PC dominate blow extrusion due to melt strength and clarity characteristics. In IBM, PETG, PP, and clarified HDPE are the most common because they produce uniform preforms and stable stretch behavior.

3. Why are core rods so critical in IBM?

Core rods define neck alignment, preform dimensions, internal air delivery, and cooling uniformity. Wear or poor cooling immediately shows up as wall-thickness variation, haze, or finish defects.

4. Can injection blow molding be used for large containers?

Typically no. IBM is optimized for small–medium containers (5 mL to ~1 L). Larger parts shift toward extrusion blow or rotational molding due to higher volume and lower precision demands.

5. What causes thread or neck-finish defects in IBM bottles?

Most finish defects trace back to neck-ring wear, core-rod misalignment, melt inconsistencies, or improper cooling during the injection stage. Even small deviations show up in closure fit and leak performance.