In injection molding, few settings influence melt quality as directly or as deceptively as barrel temperature control. Barrel temperature settings determine how consistently the screw develops melt, but they are only one piece of the melt-preparation equation.

Processors know the symptoms when the barrel profile is wrong: unmelt showing up in the part, splay from trapped moisture, drool and stringing at the nozzle, burn marks from overheated zones, viscosity swings, and intermittent short shots that seem to appear without warning.

The complication is that the barrel temperature ≠ melt temperature.

Even when every zone reads perfectly on the controller, the actual melt temperature is governed far more by shear, screw design, backpressure, and residence time than by heater bands.

That gap between displayed temperature and true melt behavior is where most processing issues originate.

This guide cuts through the guesswork.

It breaks down each barrel zone’s function, how temperature profiles influence melt development, the real physics behind melting, how to diagnose temperature-related defects, and what “good” barrel control looks like in day-to-day production.

If you need a practical, engineering-level reference for improving thermal stability and melt consistency, this is it.

Key Takeaways

Barrel temperature settings influence melting, but the actual melt temperature is driven mainly by shear, screw design, backpressure, and residence time.

Each barrel zone has a distinct function: feed (conveyance), compression (melting), metering (homogenization), and nozzle (flow control)—and incorrect zone temps cause unmelt, splay, burn, drool, and short shots.

Temperature profiles (ramp, flat, reverse) must match resin behavior; wrong profiles create viscosity swings and inconsistent part quality.

Most “temperature-related defects” trace back to poor melting, worn screws/NRVs, low backpressure, or shear imbalance, not heater settings.

MD Plastics improves melt stability upstream, making barrel temperature control easier and more predictable through advanced screws, NRVs, and real melt-monitoring tools.

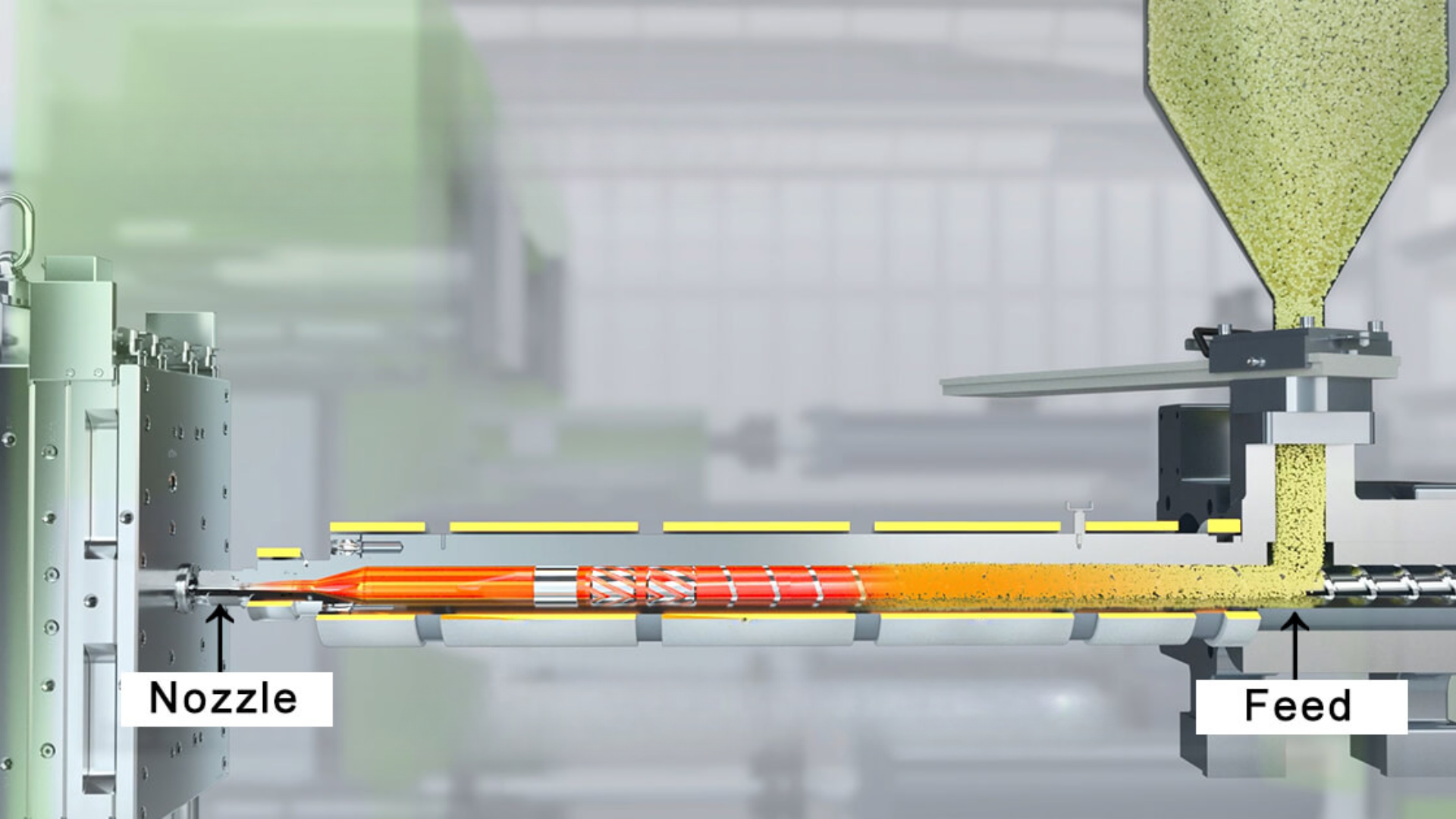

Injection Molding Barrel Zones Explained

An injection molding barrel isn’t just a heated tube; it’s a staged thermal and mechanical environment divided into zones, each designed to perform a specific step in the transition from pellets → softened pellets → melt → homogeneous melt.

The temperature “profile” across these zones, not any individual setting, determines how smoothly the screw develops a stable, repeatable melt.

Below is the engineering breakdown of each zone and how its temperature influences real melt behavior.

(Zone 1) Feed Zone: Solid Conveyance + Initial Softening

Location: Directly beneath the hopper; the beginning of the barrel.

Typical Temperature Strategy: Lower than downstream zones; sometimes intentionally “cold” depending on resin (e.g., PP, HDPE) to prevent premature melting.

Role:

Prevent bridging and pellet sticking at the hopper throat.

Ensure consistent, solid conveying into the compression section.

Begin slight outer-layer softening to aid mechanical conveying without melting the pellet core.

Impact on Melt Quality:

Too hot:

Pellets stick to the barrel → screw starvation

Surging and inconsistent melt density

Early melt → poor compression and unstable viscosity

Too cold:

Un-melt carries into the compression zone

Screw torque spikes

Pellet grinding → dust → discoloration or contamination

Defects Caused by Wrong Feed-Zone Settings:

Splay from trapped moisture

Silver streaking

Melt/color uniformity issues

Surging due to stick–slip conveying

(Zone 2) Compression Zone: Primary Melting & Energy Input

Location: Middle section of the barrel, where the screw’s channel depth begins to reduce.

Typical Temperature Strategy: Warmer than Zone 1 to begin melting aggressively, but not so hot that pellets melt prematurely or create an early melt pool.

Role:

This is where most melting actually occurs.

Pellets collapse and transition into a molten pool.

Screw geometry (compression ratio, channel depth reduction) applies shear, generating the bulk of thermal energy.

Impact on Melt Quality:

Zone 2 temperature complements shear; it cannot replace it.

If too cold:

Unmelted particles remain in the melt pool

Flow lines and black specs

Higher injection pressure required

If too hot:

Early melt causes screw inefficiency

Shear overheating → yellowing, burn marks

Resin degradation in long residence-time runs

Troubleshooting Indicators

Unmelt specks → Zone 2 too cold or insufficient backpressure

Degradation/yellowing → Zone 2 too hot or long residence time

Rising torque → feed zone too cold or resin moisture

(Zone 3) Metering Zone: Homogenization + Viscosity Stabilization

Location: Downstream end of the barrel, just before the front zone/nozzle.

Typical Temperature Strategy: Slightly hotter or equal to Zone 2, depending on resin; target is a stable, fully molten, homogeneous melt.

Role:

The final stage of melting refines the melt to an even, predictable consistency.

Homogenizes pigments, additives, and recycled content.

Establishes melt viscosity entering the front zone and nozzle.

Impact on Melt Quality:

Direct influence on shot-to-shot repeatability.

Too hot:

Drool/stringing at the nozzle

Overly fluid melt → over-packing → flash

Too cold:

Viscosity spikes

Pressure-limited shots

Fill the imbalance in multi-cavity molds

Defects from Incorrect Metering-Zone Settings:

Short shots

Hesitation marks

Cavity-to-cavity dimensional drift

(Zone 4) Nozzle Zone: Flow, Drool Prevention, Gate Freeze Behavior

Location: At the barrel exit, directly before the sprue bushing or hot runner.

Typical Temperature Strategy: Often equal to or slightly hotter than Zone 3 for shear-sensitive resins; sometimes slightly cooler for drool control.

Role:

Maintain melt temperature consistency right before injection.

Prevent premature cooling at the tip.

Provide a stable flow into the gate without degradation or freeze-off.

Impact on Melt Quality:

Too hot:

Drool/stringing

Gate smear

Stringing as the mold opens

Higher risk of burn on shear-sensitive materials

Too cold:

Cold slugs

Flow lines and hesitation

Early gate freeze-off → short shots

Special Processing Notes

PC/PMMA: nozzle is often the hottest zone

TPE/PE: nozzle sometimes runs cooler to prevent drool

Hot runners: nozzle zone becomes more critical for gate freeze timing

Understanding each barrel zone’s role allows processors to diagnose melt inconsistencies faster and set temperatures based on polymer behavior, not outdated machine charts or guesswork.

Barrel Temperature vs Actual Melt Temperature

One of the most common misconceptions in injection molding is assuming that the numbers on the barrel’s heater bands equal the melt temperature inside the screw channel.

They don’t; not even close.

Barrel temperature influences melt, but the melt temperature you measure at the nozzle or with a probe is determined primarily by mechanical energy, not heater setpoints.

What Actually Controls Melt Temperature

The melt temperature is shaped far more by shear and material behavior than by heater bands:

Screw shear: the main source of heat generation

Backpressure: increases shear + mixing → raises melt temperature

Screw design: compression ratio, flight depth, mixing elements

Residence time: longer residence time raises the melt temperature and risk of degradation

Moisture and additives: influence viscosity and shear sensitivity

This is why two machines with identical barrel profiles can produce melts that differ by 20–40°F.

Why Barrel Zones Can Be “Perfect” but Melt Temperature Is Still Wrong

Because heater bands only affect the barrel wall, not the melt itself.

Common scenarios:

Melt reads too hot, even with moderate heater settings → shear is excessive

Melt reads too cold despite high heater settings → insufficient shear, worn screw, worn NRV

Melt uniformity looks poor → backpressure too low or screw design mismatched to resin

Melt appears stable during idle, but drifts during production → shear heating changes under load

Heater displays tell you what the steel is doing.

They do not tell you what the polymer is experiencing.

Why Relying on Heater Setpoints Gives False Confidence

Heater-band temperatures:

Don’t account for shear variation during the plasticizing cycle

Don’t reflect screw/barrel wear

Don’t show melt-temperature gradients across the melt pool

Don’t reveal viscosity swings that cause pressure instabilities

This is why some processors “chase the heaters” when defects appear, even though the root cause is mechanical, not thermal.

Why Real Processors Measure Melt with a Probe

A melt probe (or MD Plastics Temp-Sense™) gives the only meaningful temperature reading:

It measures polymer temperature directly at the nozzle or the end of the barrel

It captures shear-induced heating that heater bands cannot measure

It reveals melt inconsistency long before quality drifts in the mold

If you’re adjusting heater zones without probing the melt, you’re tuning blind.

The contrast below shows why processors who rely only on heater-band readings often misdiagnose melt-temperature problems.

What Processors THINK Controls Melt | What ACTUALLY Controls Melt |

|---|---|

Barrel heater setpoints | Screw shear + compression ratio |

Zone temperatures | Backpressure |

Nozzle temp alone | Residence time |

“Band cycling stability” | Material moisture & additives |

Heater uniformity across zones | Screw/barrel wear |

Even when processors understand that shear, not the heater bands, controls melt, another trap still causes major instability: assuming heater bands deliver steady, accurate heat.

They don’t.

In real production, heater bands cycle, drift, override, and lag, which introduces thermal noise into the melt long before shear ever compensates for it.

That brings us to one of the most overlooked causes of inconsistent melt temperature:

Heater Band Cycling, Overrides & Thermal Lag

Heater bands do not provide continuous heat. They pulse, overshoot, lose contact, and sometimes fight your setpoints. If you rely on their displayed temperature alone, you’ll misdiagnose melt problems almost every time.

Heater Band Cycling, Why ON/OFF Behavior Creates Melt Instability

Heater bands maintain temperature by switching ON to add heat, then OFF as the barrel cools. This constant cycling creates a barrel-wall temperature ripple that the melt “feels” as inconsistency.

Why bands cycle:

PID control pulsing to maintain temperature

Poor band-to-barrel contact

Heat loss differences across zones

Why it matters:

Fast cycling = unstable melt temperature

Long ON-time = weak or failing heater band

Uneven cycling zone-to-zone = uneven thermal conditions for melting

A band can show perfect numbers while the melt is drifting 20–40°F.

Temperature Overrides: When the Machine Ignores Your Setpoint

Older machines or stressed heater circuits sometimes override the operator’s programmed temperature.

Overrides occur when:

A band cannot hit the setpoint

A thermocouple senses abnormal drift

The controller throttles output to prevent overheating

Adjacent zones compensate for a weak band

Why it matters:

Overrides disguise real hardware issues

Melt temperature becomes unpredictable

Processors often “chase the heaters” instead of finding the failed zone

Thermal Lag, Why the Display Reads 450°F, but the Melt Is 390°F

Thermal lag is the difference between the heater-band temperature and the actual melt temperature.

Causes:

Air gaps between band and barrel

Oxidation/resin buildup insulating the barrel

Worn screws generate less shear

Poor insulation is forcing bands to overwork

Thermocouples reading the barrel wall—not the melt

Result: Perfect barrel temps + unstable melt = classic thermal lag problem.

Quick Heater Band Inspection Checklist

A fast maintenance audit that prevents 80% of heater-related melt swings:

Check contact: Bands must sit flush with no air gaps.

Check cleanliness: Remove oxidation, rust, or resin char between band and barrel.

Check thermocouples: Ensure tight seating; loose sensors read ambient air.

Check amperage: Uneven draw indicates a failing band or bad SSR.

Simple inspections prevent months of unnecessary “temperature adjusting.”

Understanding how heater bands behave in the real world makes one thing clear:

The temperature profile you set is not necessarily the profile your melt experiences.

Now that we’ve covered how hardware influences heat delivery, the next step is choosing the correct barrel temperature profile for your resin and melt behavior.

Correct Barrel Temperature Profiles

Barrel temperatures aren’t just numbers; they’re a thermal strategy. The profile you choose determines how pellets soften, how melt develops, and how consistently viscosity stays from shot to shot.

Below are the three primary profiles processors use and when each one makes sense.

Standard Ramp Profile

Most common; increases temperature from Feed → Compression → Metering → Nozzle

Best for: PP, PS, ABS, many general-purpose resins.

Why it works: A gradual temperature increase matches the screw’s melting mechanics—pellets soften slowly in Zone 1, collapse in Zone 2, and refine in Zone 3.

Benefits:

Predictable melt progression

Good control over viscosity for mid-range shear materials

Prevents premature melting in the feed zone

Risks:

If the ramp is too aggressive, the front zone overheats → degradation, yellowing, burn marks

Excess front-zone heat can also increase drool/stringing

Flat Profile

All barrel zones run at or near the same temperature

Best for: Shear-sensitive resins such as PC, PMMA, and some TPUs.

Why it works: These polymers develop most of their melt energy from shear, not temperature, so the barrel simply needs to maintain a stable, uniform environment.

Benefits:

Excellent melt uniformity

Reduces the risk of thermal degradation at the front

Helps maintain color stability in sensitive materials

Risks:

Requires consistent screw shear; if the screw design is weak or the backpressure is low, you can get unmelt or poor mixing

Flat profiles amplify any upstream issues in melting

Reverse Profile

Zone 1 hottest → temperatures gradually drop toward Zone 3

Best for: High-viscosity resins, tacky pellets, and moisture-sensitive nylons (PA6/PA66) are used when feed-zone slippage is a problem.

Why it works: A hotter Zone 1 improves solid conveying and prevents pellets from slipping or “stalling.” Downstream zones run cooler to control final viscosity.

Benefits:

Stabilizes feed for slippery or low-friction pellets

Reduces screw surging in high-viscosity resins

Helps dry sensitive nylons by increasing early thermal input

Risks:

Easy to overheat Zone 1 → bridging, sticking, screw starvation

If downstream temps are too low → unmelt, pressure spikes

Rarely used unless the material demands it

Recommended Profile by Resin (Quick Reference)

Resin | Best Temperature Profile | Reasoning |

|---|---|---|

PP | Standard Ramp | Predictable melting, stable viscosity, prevents feed-zone tack. |

PS | Standard Ramp | Low shear sensitivity; benefits from progressive heating. |

ABS | Standard Ramp (mild) | Avoids front-zone overheating that causes yellowing. |

HDPE / LDPE | Standard Ramp | Prevents premature melt in feed zone; controls drool. |

PC | Flat | Highly shear-sensitive; uniform thermal environment required. |

PMMA | Flat | Reduces risk of burn or discoloration. |

Nylon (PA6/PA66) | Reverse or Mild Ramp | Helps with feed slippage; requires moisture-sensitive control. |

POM | Standard Ramp | Stable crystalline melt development; avoid overheating. |

TPU | Flat | Sensitive to thermal degradation; uniform heating preferred. |

GF Nylons | Mild Ramp or Reverse | Higher viscosity + abrasive; needs stronger early conveying. |

The fastest way to validate (or correct) a temperature strategy is to troubleshoot the defects it creates: unmelt, splay, drool, burn, short shots, and viscosity shifts.

The diagnostic chart below connects each defect directly to its most likely barrel-temperature cause.

Injection Molding Temperature-Related Defects: Causes & Fixes

Defect | Likely Temperature-Related Cause | Corrective Action (explicit) |

|---|---|---|

Splay/silver streaks | Feed zone too cold; wet resin; low shear → low actual melt temp | Raise Zone 1 slightly, dry resin/verify dryer, increase screw RPM to add shear, reduce decompression if pulling air |

Unmelt particles/specs | Zone 2 too cold; low backpressure; worn screw → poor melting | Raise Zone 2, increase backpressure 25–50 psi, increase screw RPM, inspect screw/barrel for wear |

Burn marks / black streaks | Zone 3 or nozzle too hot; long residence time; over-shear | Lower Zone 3 & nozzle temps, shorten recovery time, reduce screw RPM/backpressure if overheating |

Short shots (temperature-driven) | Front zone/nozzle too cold; high viscosity; cold slug at nozzle | Raise Zone 3 & nozzle temps, increase backpressure, purge cold slug, reduce decompression |

Drool / stringing at the nozzle | Nozzle too hot; metering zone too hot; excessive decompression | Lower nozzle 5–10 °C, trim Zone 3, reduce decompression, add suck-back delay |

Color swirl / poor mixing | Metering zone too cold; low shear; low backpressure | Raise Zone 3, increase RPM, increase backpressure, verify masterbatch let-down |

Jetting / flow lines | Front too cold → high viscosity jet; nozzle too cold; injection too fast with cold melt | Raise nozzle/Zone 3, warm gate area, slightly reduce V→P transfer speed, ensure proper melt temp |

Hesitation marks / flow hesitation | Temperature gradient across zones; front cooler than mid; variable viscosity | Flatten Zone 2→3 profile, raise Zone 3, stabilize screw recovery (RPM/backpressure) |

Gate blush/smear | Nozzle too hot; melt too hot at entry | Lower nozzle, lower Zone 3 a few degrees, optimize decompression/start-of-injection timing |

Cold slug / freeze-off at the gate | Nozzle too cold; long sprue exposure; front band cycling | Increase nozzle temp, insulate sprue/nozzle, verify band function & contact |

Voids/bubbles (thermal origin) | Melt too cold when packing; gas stays; moisture | Raise Zone 3, increase pack pressure/time, dry resin, reduce injection speed if entraining air |

Sink (temperature-related) | Melt too cold → poor packing; front zone cools early | Raise Zone 3, raise mold temp if allowed, extend/raise pack, ensure consistent melt density (backpressure) |

Warp (thermal) | Non-uniform melt temp; inconsistent recovery heat; hot spots in front | Stabilize Zone 2–3, reduce RPM if overheating, tighten melt temp window (measure actual melt) |

Gloss/haze variation | Inconsistent melt temp shot-to-shot; nozzle temp swings | Tighten Zone 3 & nozzle control, replace cycling bands/relays, insulate nozzle, stabilize recovery |

Dimensional drift (over time) | Melt temp creeping up/down; heater band cycling; residence-time changes | Audit heater band cycling, verify melt with probe, lock recovery time, trim Zone 3/nozzle 2–5 °C |

Cavity imbalance (multi-cavity) | Melt temp non-uniform → viscosity split; front zone instability | Tighten Zone 3 control, stabilize backpressure/RPM, verify hot-runner temps if used, measure actual melt |

Cycle-time creep (thermal) | Response lag/overrides; poor insulation; bands cycling hard | Replace/seat bands, add barrel insulation, check power zones/SSR, reduce setpoints if overshooting |

Quick reality check

Barrel setpoints ≠ melt temperature. If fixes don’t stick, measure actual melt at the nozzle (pyrometer/needle probe) and adjust Zone 2–3, RPM, and backpressure to hit the true melt window for the resin.

90% of “temperature defects” resolve by dialing Zone 2 (melting), Zone 3 (metering), backpressure, and screw RPM, not just the nozzle.

How MD Plastics Improves Barrel Temperature Control

Barrel temperature control works only when the melt entering each zone is already stable. Most “temperature problems” actually originate in the plasticating system, screw shear, NRV sealing, and melt homogeneity, not in the heater bands.

MD Plastics strengthens the part of the machine that creates melt quality, making temperature control far more predictable.

1. Why Melt Quality Begins Upstream

Barrel zones regulate heat, but they cannot fix poor melting.

Shear, compression ratio, and mixing elements generate most of the melt energy.

When these are inconsistent, processors end up chasing temperatures that can never stabilize.

Stable melt → stable viscosity → easier barrel temperature control.

2. Components That Improve Melt Consistency

Custom Screws: Generate uniform shear and melting, reducing unmelt and viscosity swings.

Precision Barrels: Improve thermal stability and reduce heater cycling.

MDP™ Non-Return Valves: Eliminate backflow, critical for consistent melt density and shot volume.

Optimized Nozzle Tips: Reduce drool, freeze-off, and cold-slug defects without overheating the front zone.

Result: Better melt quality with less dependence on extreme temperature profiles.

3. Real Melt Monitoring (Melt-Profiler™, Melt-IQ®, Temp-Sense™)

Heater readings show steel temperature, not polymer temperature.

MD Plastics’ monitoring tools measure:

Actual melt temperature

Shear-induced heat

Viscosity stability

Early wear indicators

This lets processors set barrel temperatures based on real melt behavior instead of guesswork.

4. Retrofit Benefits

Upgrading only the plasticating end can immediately improve:

Melt-temperature stability

Start-up repeatability

Shot consistency

Sensitivity to heater-band cycling

Most plants achieve major gains without buying a new machine.

Conclusion

Barrel temperature settings matter, but melt physics matter more. Heater bands influence the barrel wall, while shear, screw geometry, backpressure, and residence time determine the melt temperature the polymer actually experiences.

When melt quality is stable, barrel zones stay stable, defects decline, and process windows tighten naturally.

Consistent melt is the foundation of injection-molding repeatability.

Stabilize the melt, and barrel control becomes easy. MD Plastics combines on-site process analysis with engineered plasticating hardware and real melt monitoring to remove upstream variability and maximize productivity.

Ready to align barrel control with true melt behavior? Book a data-driven melt evaluation.

FAQs

1. What is the purpose of each barrel zone in injection molding?

Each zone performs a different thermal function:

Zone 1 (Feed): solid conveying + controlled softening

Zone 2 (Compression): primary melting and shear generation

Zone 3 (Metering): homogenization and viscosity stabilization

Zone 4 (Nozzle): flow control, drool prevention, and gate freeze management

Together, they manage pellet transition from solid → melt → consistent melt.

2. Why doesn’t the barrel temperature match the actual melt temperature?

Because heater bands heat steel, not polymer. Actual melt temperature is shaped mainly by:

shear energy

screw design

backpressure

residence time

It’s common for melt temperature to be 20–40°F different from barrel readings.

3. What temperature profile should I use for PP/ABS/PC/etc?

General guidance:

PP, PS, ABS → Standard Ramp

PC, PMMA → Flat

Nylons, tacky pellets → Reverse or Mild Ramp

Profiles should always be validated with actual melt-temperature measurement, not just heater displays.

4. How do I know if my barrel zones are too hot or too cold?

Typical indicators:

Too cold: unmelt, high injection pressure, hesitation, short shots

Too hot: drool, stringing, burn marks, discoloration

Confirm with a melt probe—zone temperatures alone can be misleading.

5. Why do heater bands cycle so frequently?

Bands cycle ON/OFF to maintain the setpoint using PID control. Heavy cycling usually means:

poor band-to-barrel contact

insulation loss

failing heater band

temperature override mode in older machines

Cycling creates thermal noise that destabilizes melt temperature.