When you’re developing a plastic part, whether it’s a housing, bracket, handle, optical feature, or functional prototype, the first major decision is choosing how to make it: CNC machining or injection molding.

Both processes are proven, both can deliver high-quality parts, and both support a wide range of polymers. But they behave very differently, and the wrong choice can cost weeks of delay or thousands in rework.

The real challenge is that the decision isn’t just about volume or budget. It comes down to:

• how tight the tolerances need to be,

• how the geometry handles melt flow versus cutting forces,

• whether the resin machines clean or molds predictably,

• and how your long-term production plan affects cost per part.

This guide breaks down those variables with practical engineering logic—tolerances, wall-thickness rules, feature limitations, tooling costs, cycle time behavior, and the break-even point where machining gives way to molding.

By the end, you’ll know exactly which process fits your part’s geometry, performance needs, and scale.

If your goal is to choose the right manufacturing method on the first try, this is the place to start.

Key Takeaways

CNC machining is best for low volumes, complex shapes, thick sections, and ultra-tight tolerances, because it cuts parts directly from solid stock without melt-flow limitations.

Injection molding is the most efficient choice for medium to high volumes, delivering fast cycles, consistent dimensions, and low cost per part once tooling is built.

Geometry decides more than people expect: machining is limited by tool access and rigidity, while molding is limited by flow, shrinkage, gating, draft, and cooling.

Material behavior often determines the process before cost does: nearly all plastics can be machined, but only thermoplastics that melt and flow predictably can be molded.

If molding is the chosen path, melt stability is the foundation of repeatable parts—MD Plastics can help ensure the melt entering the mold is uniform, stable, and production-ready.

CNC vs. Injection Molding at a Glance

Note: Bookmark This

If you need the answer fast, this table captures the real engineering trade-offs between CNC machining and injection molding. It’s the snapshot you can use when narrowing manufacturing options.

Factor | CNC Machining | Injection Molding |

|---|---|---|

Volume Fit | Best for 1–500 parts | Best for 5,000+ parts |

Tooling Cost | Low (fixtures only) | High (mold cost dominates) |

Unit Cost | High, each part machined | Low, cycle-based production |

Tolerances | Very tight (±0.001 in typical) | Tight (resin- and mold-dependent) |

Geometry Limits | 3-axis/5-axis constraints; sharp edges possible | Moldability rules: draft, uniform walls, no undercuts without side-actions |

Material Options | Nearly any plastic, including filled, brittle, high-temp grades | Only moldable thermoplastics (flow + shrink constraints) |

Part Strength | Isotropic (machined from solid stock) | Anisotropic (flow lines, knit lines) |

Surface Finish | Excellent; reachable features depend on tool access | Excellent on cosmetic surfaces; limited by mold texture + flow |

Speed Per Part | Slower, each part is individually cut | Very fast, seconds per cycle |

Best For | Prototypes, low-volume runs, custom fixtures, structural components | High-volume production, consumer parts, repeatable housings, closures |

How CNC Machining Works

CNC machining is a subtractive manufacturing process that shapes plastic parts by removing material from a solid block (sheet, rod, billet). Unlike molding, where polymer flows into a cavity, CNC allows the geometry to be carved directly, making it ideal for prototypes, thick sections, and parts that can’t be molded.

How the Process Actually Works:

1. Toolpaths (CAM-Generated Cutting Paths)

A CAM program converts the 3D model into a sequence of movements, contours, pockets, drilling, and surfacing.

Toolpath strategy controls finish quality, cycle time, and dimensional accuracy.

2. Workholding (How the Part Is Fixtured)

Plastic stock is clamped using vises, soft jaws, vacuum fixtures, or sacrificial plates.

Rigid workholding prevents chatter and movement, which plastics are especially sensitive to because they deflect more than metals.

3. Chip Formation & Heat Removal

Plastic machining relies on:

Sharp tools

High rake angles

Adequate chip evacuation

Low cutting heat

Unlike metals that dissipate heat, plastics trap heat → increasing the risk of melting, deformation, or dimensional drift.

4. Suitable Part Sizes

CNC excels at:

Small to medium-sized parts

Thick walls

Parts with varying wall thickness

Components requiring deep pockets or precise bores

Large thin-walled parts are more challenging due to deflection.

Why Machining Plastics Behaves Differently

Plastics aren’t just “softer metals”; they respond differently under cutting forces:

Thermal softening: Heat quickly softens thermoplastics, causing melting or smearing.

Burr formation: Common in materials like ABS, nylon, or UHMW.

Swelling & moisture absorption: Nylon and acetal can change dimensions after machining.

Stress whitening: Acrylic, PC, and PMMA show white “frosting” at high cutting loads.

Elastic recovery: Plastics “bounce back” after cutting, affecting tolerances.

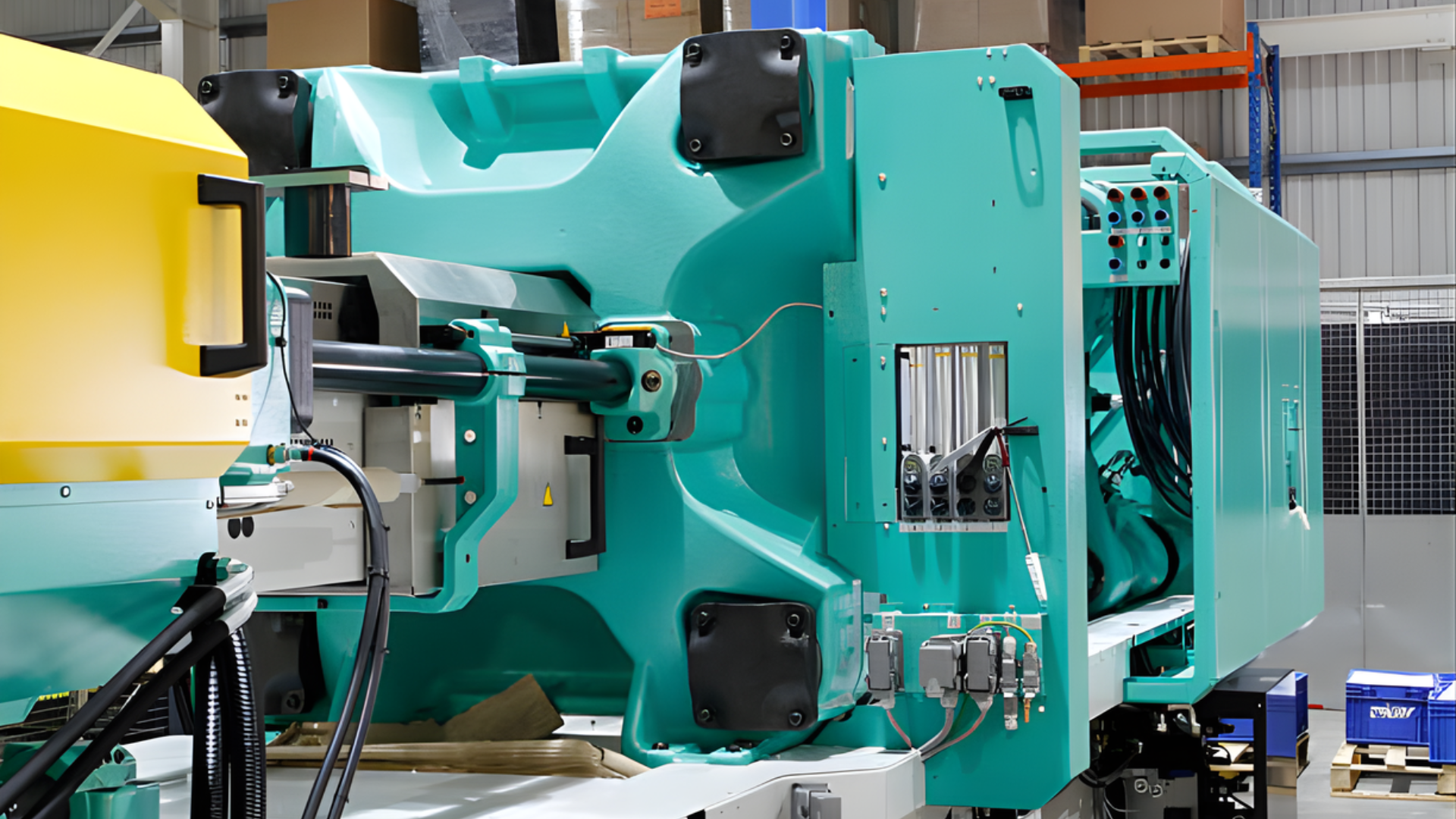

How Injection Molding Works

Injection molding creates plastic parts by melting resin, injecting it into a steel mold, and repeating that cycle thousands or millions of times with near-identical results. It’s the opposite of machining: instead of removing material, you fill a precision cavity.

Plasticizing (Preparing the Melt)

Pellets enter the heated barrel, where the screw:

melts the resin,

mixes pigments/additives, and

meters the shot for the next cycle.

Melt quality, temperature uniformity, viscosity stability, and shear history determine how the part will fill and how consistent each shot will be.

Injection → Packing → Cooling → Ejection (The Full Cycle)

Injection:

The screw drives forward, pushing molten plastic into the mold cavity at a controlled velocity.

Packing:

Additional pressure compensates for shrinkage as the polymer solidifies.

This step controls final dimensions, sink marks, and density.

Cooling:

The mold’s internal water channels extract heat until the part is rigid enough to eject.

Cooling is the longest portion of the cycle and heavily influences productivity.

Ejection:

Pins or plates push the part out, and the mold closes to begin the next shot.

Why the Mold Defines 80% of Geometry Limits

The mold determines:

parting line location

gate placement

wall thickness feasibility

draft angles

rib proportions

undercuts and side-actions

If a feature isn’t moldable, no processing adjustment can compensate for it—design must respect moldability rules.

Why Injection Molding Beats CNC in Repeatability

Injection molding produces parts with:

consistent cavity packing,

stable melt delivery,

fixed steel geometry, and

tightly controlled cooling.

This means dimensional variation is measured in hundredths of a millimeter across tens of thousands of cycles, repeatability CNC cannot match on a per-part basis.

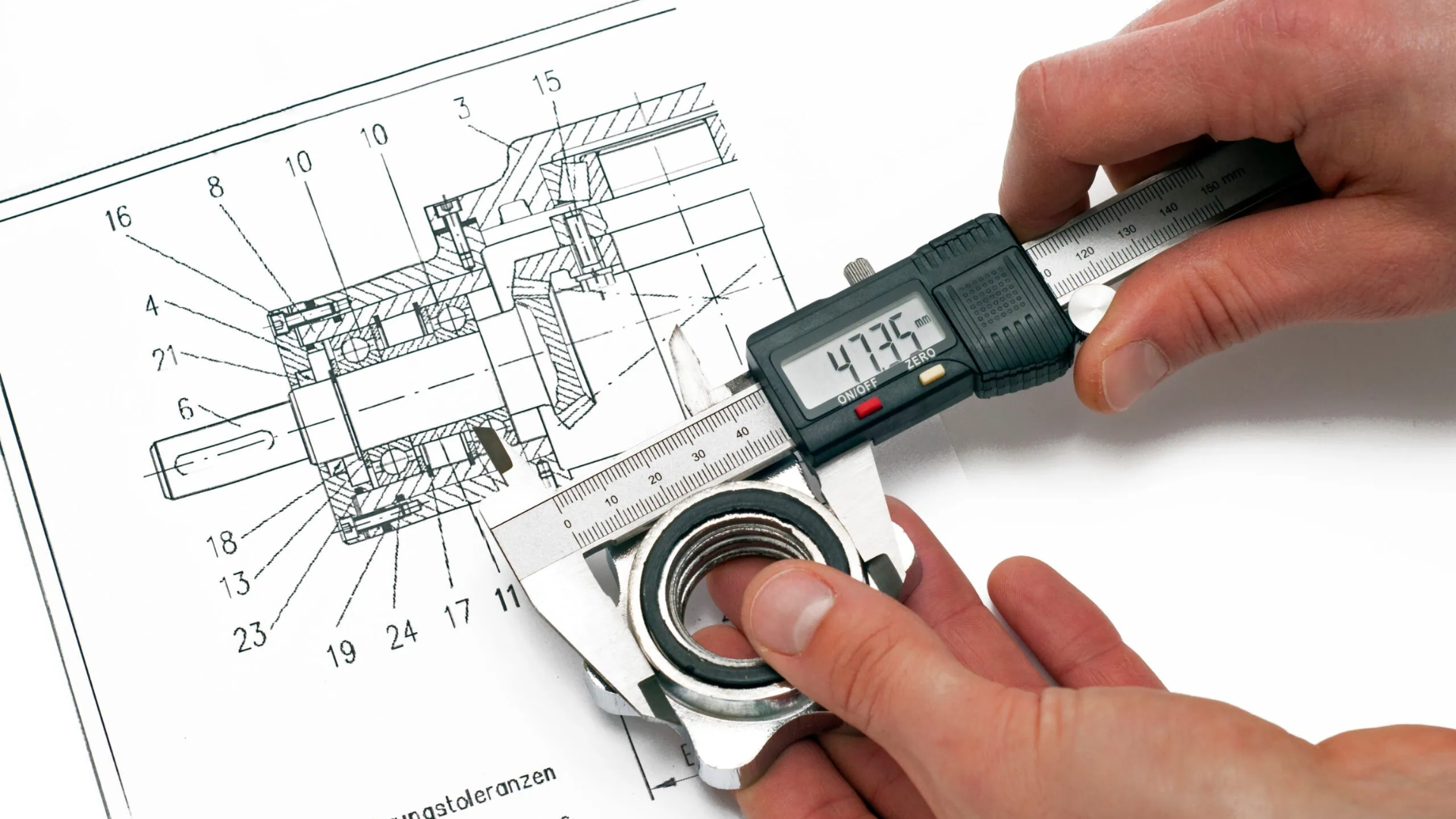

Tolerances: CNC vs. Injection Molding

CNC Machining Tolerances

CNC machining achieves tight precision because features are cut directly from solid material.

±0.001 in (0.025 mm) is a common, reliable production tolerance

±0.0005 in (0.012 mm) or tighter is achievable with controlled environments and optimized toolpaths

Influenced by:

tool wear

workholding rigidity

thermal expansion in plastics

spindle accuracy

chip evacuation and heat buildup

Injection Molding Tolerances

Injection molding precision depends on mold construction, melt stability, cooling uniformity, and part geometry.

±0.002–0.005 in (0.05–0.12 mm) typical for most production molds

±0.001 in (0.025 mm) possible with:

high-stability melt preparation

hardened steel tooling

well-balanced gating

optimized cooling circuits

low-shrink engineering resins

Key influences include:

melt temperature consistency

cavity-to-cavity balance

tool steel accuracy

shrink characteristics of the resin

cooling layout and uniformity

Injection molding tolerances depend heavily on melt stability; variations in temperature, viscosity, or pressure are often the root cause of drift.

If tolerance consistency is becoming difficult to maintain, MD Plastics can review the melt delivery side of your process and recommend targeted improvements.

Geometry & Design Constraints

CNC Machining Geometry Limits

Machining removes material with rotating tools, so geometry is constrained by cutter shape, rigidity, and heat behavior.

Undercuts require special tooling, such as T-slot, lollipop, or custom ground tools

Thin walls can vibrate, chatter, or soften when machining plastics

Deep pockets increase tool deflection and reduce dimensional accuracy

Sharp internal corners are impossible; every end mill leaves a radius

Burrs are common in softer polymers (PE, PP, UHMW), requiring secondary deburring

Very small features become limited by tool diameter, spindle speed, and heat generation

Injection Molding Geometry Limits

Molding creates parts by filling a steel cavity with molten resin, so part design is governed by flow, shrinkage, and ejection behavior.

Walls must stay uniform to avoid sink, warp, and differential shrinkage

Draft angles are mandatory on most vertical surfaces for reliable ejection

Undercuts require side actions, lifters, or collapsible cores

Thin walls depend on resin flowability and gate type/position

Gate placement affects cosmetic surfaces and weld-line visibility

Flow orientation influences mechanical strength, especially in semi-crystalline materials

Ribs, bosses, and transitions must follow DFM ratios to prevent sinks and voids

This difference matters because CNC machining is fundamentally shape-limited; whatever the cutter can physically reach, it can create.

Injection molding is flow-limited; the geometry must allow molten resin to fill, pack, cool, and eject without distortion.

This distinction alone often determines the best manufacturing method long before cost or volume enter the conversation.

Material Constraints: What You Can and Cannot Use

Material choice often decides the process before geometry or cost. CNC machining and injection molding handle plastics very differently because one removes material, and the other melts and flows it.

CNC Machining: Material Flexibility Is Extremely High

Machining can cut almost any rigid engineering plastic:

PEEK

PTFE

UHMW

Acetal (Delrin)

Nylon

PVC

Polycarbonate

Acrylic

Glass-filled polymers (with aggressive tool wear)

Key considerations:

Heat-sensitive plastics may soften, smear, or stress-whiten if feeds/speeds aren’t controlled.

Softer materials like HDPE or PP can burr heavily and require deburring or cryogenic finishing.

Machining wins when the material is difficult to melt, degrades easily, or requires extremely small volumes.

Injection Molding: Material Must Melt, Flow, Pack, and Cool Properly

Moldable resins need to be thermally stable and capable of filling a cavity under pressure:

PP

PS

ABS

PC

Nylon (PA6/PA66)

TPE / TPU

PE (HDPE/LDPE)

PETG (if viscosity is appropriate)

High-temperature resins (PEEK, PSU, LCP, PPS) can also be molded, but require:

High-temp tooling

Corrosion-resistant steels

Very precise thermal control

Not all “machinable” plastics are moldable, and vice versa.

Materials That Are Especially Sensitive to Melt Quality

These resins demand precise thermal and shear control during plasticizing:

Polycarbonate (PC): clarity and toughness depend on tight melt-temperature windows

Nylon (PA): absorbs moisture; the melt viscosity can swing rapidly

PETG: extremely clarity-sensitive

Filled resins (GF, mineral-filled): wear the screw/NRV faster, need stable melt prep

This is exactly where melt-conditioning hardware matters most and where MD Plastics’ screw, barrel, and NRV designs improve part consistency.

Cost Comparison

Cost is usually where CNC machining and injection molding diverge the fastest. One method spends money on time, the other on tooling. Understanding that tradeoff makes the break-even point easy to calculate.

CNC Machining: What Drives Cost

Time per part (feeds, speeds, toolpath length)

Tool wear (end mills, drills, inserts)

Fixturing and setup

Operator involvement

Scrap from machining thin or flexible plastics

Result: Great for low volume, but the price per part stays high.

Injection Molding: What Drives Cost

Tooling investment (steel, machining, polishing, gating, cooling circuits)

Mold setup & qualification

Resin cost per shot

Cycle time (seconds per part, not minutes)

Result: High upfront cost, but extremely low cost per part.

Break-Even Example

Method | Cost Structure | Example Cost |

|---|---|---|

CNC Machining | ~$40 per part | $40 × Qty |

Injection Molding | ~$2 per part + $10,000 tooling | $10,000 + ($2 × Qty) |

Typical break-even: ~300–700 parts, depending on:

part size

complexity

tolerance class

resin behavior

surface finish

Below a few hundred units → CNC wins.

Above that range → molding becomes dramatically cheaper per piece.

Production Speed, Repeatability & Scalability

CNC Machining

Slower, part-by-part production, each component requires its own toolpath and cycle.

Ideal for low-volume runs where flexibility and quick setup matter more than throughput.

Automation is possible but limited, especially for multi-op parts or plastics prone to deformation.

Injection Molding

Cycles are measured in seconds, producing finished parts at a rate CNC simply cannot match.

Exceptional repeatability, because every shot comes from the same melt, mold, and cooling conditions.

Scales effortlessly from hundreds to millions of units without changing the fundamental process.

Takeaway: CNC excels in flexibility; molding dominates once speed and consistency become priorities.

Defects: CNC vs Injection Molding Failure Modes

CNC Machining Defects

Even with precise toolpaths, plastics are unpredictable under cutting forces and heat. Common issues include:

Burrs at edges, especially on softer resins like PP or HDPE.

Heat-induced warpage from poor chip evacuation or aggressive feeds.

Tapered or out-of-square walls are caused by tool deflection in deep pockets.

Tool marks and chatter patterns on cosmetic surfaces.

Cracking or stress-whitening in brittle plastics like acrylic or PS.

Injection Molding Defects

Molded parts fail for entirely different reasons, nearly all tied to melt behavior, cooling uniformity, or mold design:

Sink from insufficient packing or thick sections.

Voids caused by trapped gases or rapid solidification.

Flow marks from inconsistent velocity or premature cooling.

Splay is linked to moisture or unstable melt temperature.

Cooling warpage due to uneven thermal extraction.

Short shots when the melt flow is restricted or viscosity spikes.

Most molding defects trace back to what happens inside the barrel, not inside the mold. When the melt is stable and uniform, the majority of these issues disappear long before the tool fills.

When to Choose CNC Machining vs. Injection Molding

Engineers often reach a decision faster once they frame the problem around volume, geometry, and material behavior. These two lists capture the practical triggers that push a project toward one process or the other.

When CNC Machining Is the Better Choice

Choose CNC machining when your parts require conditions that molding simply can’t deliver:

Low-volume production where tooling investment isn’t justified

Highly complex or deep features that can’t be molded without slides/unscrewing actions

Thick, solid, or fully dense parts that would sink or warp in a mold

Plastics that degrade when melted (PTFE, UHMW, certain high-crystallinity materials)

Prototype or evolving designs where rapid iteration matters

Extremely tight tolerances, beyond what molded shrinkage can reliably achieve

CNC offers flexibility without the constraints of flow, gating, or cooling, making it ideal for early-stage development and specialty geometries.

When Injection Molding Is the Better Choice

Injection molding becomes the clear winner once scalability and repeatability enter the equation:

Production volumes above ~500–1,000 parts

Parts that must match exactly from run to run

Cosmetic surfaces, gloss, or tight color matching

Geometry that benefits from flow orientation (living hinges, thin walls)

Programs requiring multi-cavity output for cost efficiency

Material grades optimized for melt processing (PP, ABS, PC, Nylon, TPEs)

If the design is stable and volumes justify tooling, molding delivers the lowest cost per part and the highest repeatability.

When injection molding is the chosen path, remember that consistent molded parts start with consistent melt. Variations in melt temperature, pressure, or viscosity show up later as dimensional drift, surface defects, or cavity imbalance.

MD Plastics helps processors stabilize melt preparation so new tooling performs as expected from the first cycle onward.

Conclusion

CNC machining and injection molding aren’t competing technologies; they solve different manufacturing problems. CNC excels when you need flexibility, fast iteration, and tight tolerances on low-volume or geometry-intensive parts.

Injection molding wins when precision, scalability, and cost efficiency matter, especially once production climbs above a few hundred units.

Across both processes, one principle stays constant: part quality is directly tied to material behavior. In molding, especially, the melt’s temperature, pressure, and viscosity define how reliably a tool can produce within tolerance.

If injection molding is the path you’re taking, it pays to stabilize melt preparation before steel is cut. Talk to MD Plastics about improving melt consistency and plasticating performance before you invest in tooling.

FAQs

1. Which is cheaper: CNC machining or injection molding?

CNC is cheaper at low volume because there’s no tooling cost. Injection molding becomes significantly cheaper once production exceeds a few hundred parts.

2. Which process is faster for production?

Injection molding. Once the tool is built, parts are produced in seconds. CNC machining remains slower because each part requires individual toolpaths.

3. Which option is better for prototypes?

CNC machining is usually preferred for prototyping thanks to fast iteration, material flexibility, and no tooling commitment.

4. What tolerances can injection molding realistically achieve?

Most molded parts fall within ±0.002–0.005 in (±0.05–0.12 mm), though tighter tolerances are possible with specialized tooling and stable melt control.

5. At what volume does injection molding become cost-effective?

Typically around 500–1,000 parts, depending on geometry, tooling complexity, and resin choice.

6. Can CNC machining and injection molding be used together?

Yes. Many teams CNC-machine prototypes, fixtures, or low-volume components, and transition to molding once the design is finalized.